In this extract from his new book, Corporate Newsman, Kaizer Nyatsumba shares a memory of life in the media during the Apartheid regime

Following an approach by retired academic and anti-Apartheid activist Professor Fatima Meer, I hosted—in partnership with her, on the premises of the Independent Group—a day-long conference on the relationship between Africans and Indians in the province and on the contribution of South Africans of Indian origin to the anti-Apartheid struggle.

Among the speakers were sociologist Professor Herbert Vilakazi, Inkosi Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Meer herself. That year, I was also invited by the University of Durban-Westville’s Faculty of Commerce to address its graduation ceremony.

One of the graduates was a member of my own staff, Martin Challenor, who had just completed his Master of Business Administration degree.

Another important development was a decision by the South African Human Rights Commission, led by Advocate Barney Pityana, to hold public hearings into racism in the media.

The Commission’s concern was prompted by some influential black voices contending that, a full five years after the dawn of democracy, various media institutions continued to be biased in their reporting on blacks in general and the black-led government in particular.

Predictably, as often happens with the media whenever attempts are made to subject the institution to the same critical scrutiny to which it subjects others, the decision was met with fierce resistance from some white colleagues and the media companies themselves. They argued, as they often do at such times, that such hearings potentially posed a threat to freedom of speech and that the media were better placed to regulate themselves and to take corrective action.

I differed sharply with such a view. In fact, I was very disappointed by the media’s hypocritical response. I knew that, as an institution, the media would have welcomed any such scrutiny of the government or any government policy. If there was one thing that I could never accept within that institution was its duplicity and holier-than-thou attitude: everything and everybody else was fair game for criticism, but not the media themselves.

In both my editorial in the Daily News and in my nationally syndicated column, I welcomed the Commission’s hearings and pledged to participate in them. I undertook to appear before the Commission not only to respond to any complaints that may have been laid against the Daily News (there was one complaint), but also to make a submission on the matter under investigation. I chose to share with the Human Rights Commission my experiences, views and observations as an African journalist and editor.

That proved to be a controversial decision within the Independent Group. During a teleconference with other editors and the business leadership in the Group, it was resolved not to participate in the Commission’s hearings. I was left with no option but to inform my colleagues that I would participate in the hearings in my capacity as a black person, and not as a representative of the organisation. I would speak at the Commission’s hearings as a senior black editorial executive with a view on the matter being investigated by the Commission.

My decision was not popular with most of my fellow editors and the business leaders within the Group, but I was certain then and am certain now that it was the right one. At the time, Cyril Madlala and I were the only African editors. Black editors included Moegsien Williams at the Cape Argus, Ryland Fisher at the Cape Times, Dennis Pather at The Mercury and Paula Fray at the Saturday Star. I was a minority of one.

My friend, Mike Siluma, was the editor of the Sowetan at the time and also happened to be the chairman of the South African National Editors’ Forum. He was an outspoken advocate for transformation within the media and, therefore, a fierce proponent of the Commission hearings. On The Star a decade earlier, he and I had led an informal group taking up black journalists’ concerns with management.

Apart from the short spell during which I was a co-opted member of the Azanian Students’ Organisation leadership in my first year at the University of Zululand, I had not belonged to many organisations in my life. I had always preferred the freedom to view things unhindered by affiliations or ideology, free to support whatever I agreed with and to criticise whatever I differed with. Both in the run-up to and beyond our founding democratic elections, I had always supported democracy, but not any one political organisation or party.

Three times the Democratic Party tried to recruit me to leave journalism to be one of its public representatives, and three times I turned it down.

The first and last approaches were made by the DP’s Mike Moriarty at Mike’s Kitchen in Parktown, when I was still a journalist. Even after I had transitioned to business, he approached me again. On both occasions, I told him I was not made for partisan politics. Another approach, while I was still on The Star, was made by the party’s leader, Tony Leon, at a restaurant at Rosebank Mall, and I told him the same thing.

Bizarrely, though, years later I learnt that a prominent DA leader had claimed that I had allegedly confided in a colleague that, as editor of the Daily News, I was on a mission to destroy him. He wrote further that I engaged in self-promotion by publishing my poems in the paper and having big posters of myself distributed everywhere with the paper’s news posters.

Implicit in this man’s view was that white editors were ethical and circumspect and knew better not to abuse, for personal gain, the publications that they edited, while I, the only black African editor of a mainstream newspaper in South Africa, knew no better and would see nothing wrong with abusing the Daily News to sell or promote my poetry. What utter hogwash, to use the late Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s favourite phrase.

It was strange that a senior leader of the then official opposition would stoop so low as to believe—and perpetuate—gossip. If I were similarly inclined, I would have published many things based on gossip during my journalistic career. His first two claims were blatant lies. Not only have I never been on a mission to destroy anybody in my life, for that is not the kind of person that I am, but I have never uttered such nonsense to anybody.

Secondly, throughout my fifteen years as a journalist, I have never published my poems in any newspaper. Instead, I have had my poems published, on their merit, in independent publications such as Staffrider and Tribute magazine. What did happen, though, is that in 1999, Johannesburg-based Vivlia Publishers published my poetry book, Silhouettes, and Tino Stefaans, a Daily News sub-editor, independently obtained a copy of the book and wrote a review that was published by the newspaper. It is entirely legitimate for newspapers to publish book reviews.

The truth is that I strongly disapproved of Tony Leon’s racist “Hit B[l]ack” campaign during the 1999 elections, a mere five years into our democracy—and I said as much. I found it strange that, in his attempt to grow his party, he would launch such a divisive campaign by rallying the country’s minorities—whites, coloureds and Indians—against the African majority. It was as if it was all fine for Africans, who had been the worst off under a policy that had so handsomely benefitted Leon and his ilk, to preach reconciliation, while the country’s minorities launched a fightback campaign against them. That was what I opposed and continue to oppose to this day.

To my bitter disappointment, former Business Day editor Peter Bruce—the same man whose right to endorse Holomisa in the 1999 elections I had defended on television, and whose offer of a column in Financial Mail, a publication owned by the competition to the Independent Group, I had previously turned down—parroted the same lie in his column in 2020 that I had published my poetry in the Daily News. When I challenged him to produce evidence of his claim, he did not do so—and could not do so because none exists.

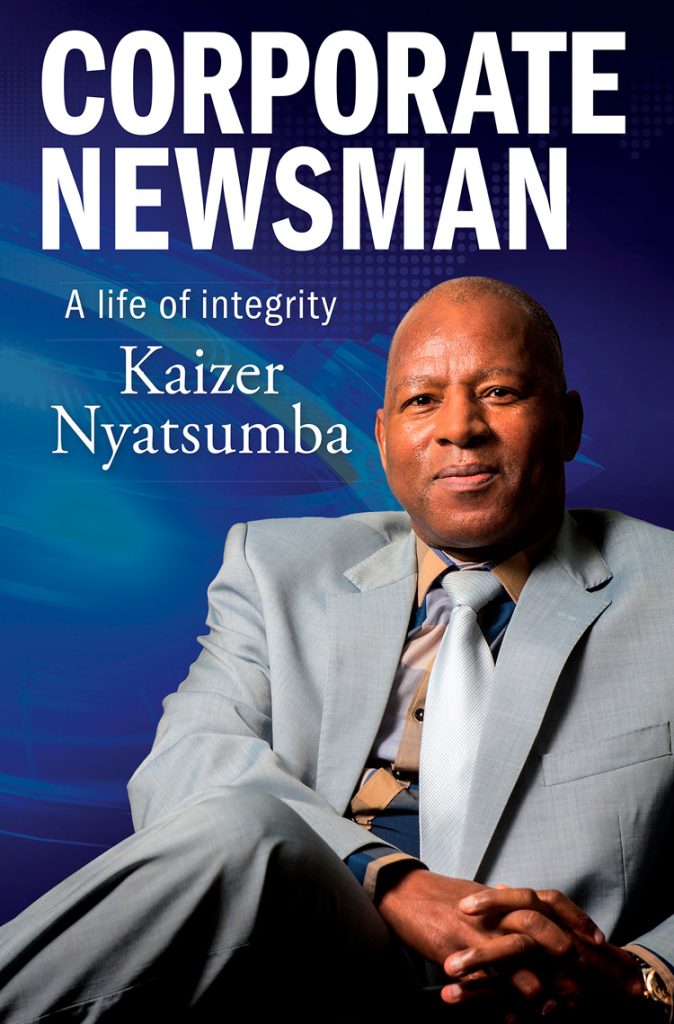

Dr Kaizer Nyatsumba is an experienced business executive who has held numerous senior leadership roles both in South Africa and the United Kingdom and has served on a number of boards.