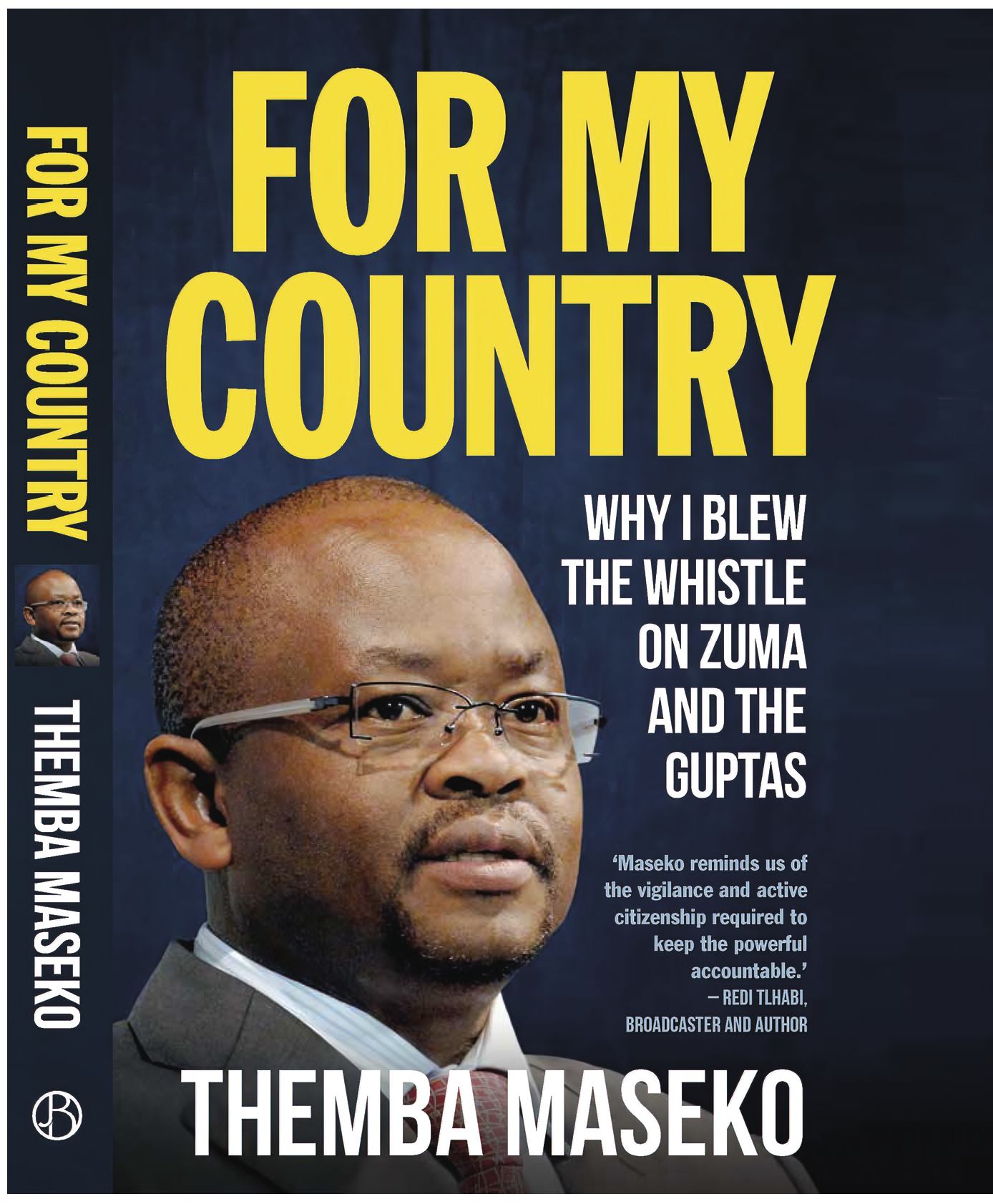

Sam Mkokeli sat down with Themba Maseko to discuss the reasoning behind the release of his memoir, For My Country: Why I Blew the Whistle on Zuma and the Guptas, and to find out more about the difficult times he faced both during apartheid and while working for the government.

Defying president Jacob Zuma came easily to Themba Maseko. Equally easy was using profanities to tell Ajay Gupta and his brother to get lost. It started with an uncomfortable phone call.

Gupta: Good evening, Mr Maseko. This is Ajay speaking.

Maseko: Good evening, Ajay.

Gupta: I hear from my people that you are being difficult.

Maseko: Ajay, that’s not true. I tried to explain to your person that I was on the road and that he should call me on Monday to set up a meeting and…

Gupta: It is very important that we meet you urgently because the matter we want to discuss can’t wait.

Maseko: Hold on, Ajay, I don’t have a problem meeting you but…

Gupta: No, no, no, this can’t wait! In fact, we can’t wait for Monday. Let’s meet tomorrow at my house.

Maseko tells this story in his memoir, For My Country: Why I Blew the Whistle on Zuma and the Guptas.

“So, when I eventually agreed to meet with Ajay Gupta, just to understand what he was trying to get from me, I got a call from president Zuma who said help these Gupta brothers. He doesn’t say exactly what help I should give them.”

Maseko went ahead with a meeting at the family’s infamous compound in Saxonwold.

“When I get to a meeting with them, they tell me that they want the whole government communication budget to be transferred into their new media company. And that’s when I realised that when Zuma said I must help the Gupta brothers, he was in a sense saying I must be part of this network of the informal, unofficial family that was giving instructions to the government.”

This event and the initial call from Zuma offended Maseko deeply.

“I felt a sense of betrayal because, in my mind, somebody who was in charge of the state should not be actively involved in acts of corruption, asking me to help the Guptas to siphon cash out of the state coffers was something that I found totally unacceptable.”

He felt helpless.

“And what was even more depressing for me was that, ordinarily, if something like that had happened, the person I should have gone to complain to was the president himself. But here was the person actually giving me some kind of advice or instruction to go and assist the family.”

Maseko shared his experience with the late Collins Chabane and other leaders in the ANC. The reluctance of people within the ANC

leadership structures to actually do anything about it at the time was even more shocking.

“I thought if something as unlawful, as corrupt, as this was happening, and the party was not willing to act, this country was in for a very rough ride.”

Maseko later spoke to the Sunday Times in what would be a key moment in lifting the lid on the extent of state capture. He is one of the main witnesses with direct allegations against Zuma at the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into state capture. Maseko describes the drama behind his dismissal.

“I knew that something was going to happen to me because I defied Zuma… I was sitting in a cabinet meeting, and during the tea break, I checked my phone, and I find tons of messages. A news channel was running with a story that, in fact, I had been fired.”

The events that followed had strong elements of a farce as Chabane performed political gymnastics to help Maseko save his bacon.

Needless to say, this created problems in the office and it was almost inevitable that Maseko quit the government soon afterwards, having agreed on a financial settlement owing to “unfair labour practice and related strife”.

His wife, children, and GCIS subordinates had all learnt through media leaks that he was no longer the country’s top spin doctor.

Likewise, at his new job, “unfortunately the staff only heard on the news that, in fact, I was the new DG. And that laid the foundation for me not staying too long because the manner in which I was actually put in the department was improper.

“There was not even an opportunity for me to be introduced to the management team or the general staff. I just arrived, and I had to find my way to tell people that they are under the new DG.”

Leaving the public service was a difficult decision for Maseko, a law school graduate who had quit his role as an MP in the 1990s so he could serve SA in a technocratic capacity.

“I was always passionate about being a public servant, being of service to the nation,” he says. At the end of his memoir, Maseko reveals that he spent three years sharing his experience only with friends and family, especially his wife.

“When I finally decided to go public with my story, it was because I saw it as my responsibility to expose the lies that were being told by Zuma and his Gupta friends. I still thought of myself as a public servant who owed his loyalty to the Constitution and to the citizens of South Africa. whose freedom I had fought for.

“However, I must confess that I did not fully realise the impact that speaking out about state capture would have on me and my family. It came at a great cost, as I soon became a professional, political, and social leper, shunned by friends and enemies alike.”

It’s been a tough journey, but at least now Maseko can go to sleep with a clear conscience every night.

“The impact of speaking out is quite huge. But it’s not an easy thing to talk about. Because the more details you give, you run the risk of scaring public servants who are in the system from speaking out, because when they start realising what the consequences are, the chances are that many of them may not speak out.”

People usually consider the financial and psychological consequences of taking on the powerful in society. “When you lose your source of income, people have to think about bonds, fees for their kids at schools, car instalments. And if you speak out and lose your job, chances are that, in fact, a lot of those things are gonna be at risk, I had to bear the responsibility of finding alternative sources of income because when you speak out, you lose your job, it becomes difficult to find employment in other parts of the public sectors.”

The ANC’s deepest values had been ingrained in him from an early age.

Maseko’s life could not have been more dramatic, including dodging bullets during the Soweto uprisings in 1976. He went on to be a leading student activist and one of the youngest MPs of the Mandela era. He had met ANC luminaries such as OR Tambo while the ANC leader was exiled in London. “I must say, I was overwhelmed by the meeting because I was meeting my hero, my idol of many years… it was probably the most monumental, memorable meeting I have ever had with any ANC leader,” he says.

Becoming a public servant was natural to him, hence he left ‘Mandela’s Parliament’ within six months of being sworn in on 26 May 1994, with the rest of the MPs that included the ANC’s most illustrious grandees.

“I was always passionate about being a public servant and being of service to the nation. And that’s why, when I was leaving university, I was active in the civil society movement.”

He was nominated by civic society groups to be on the ANC’s historic list of MPs. “And that’s how I ended up in parliament. And, after six months in parliament, I knew I did not want to sit in parliament and participate in debates and discussions, which in my view, were not as productive as they could have been. And that’s when I decided I must find another avenue of saving the nation, other than being an MP.”

He applied and got appointed as Gauteng’s first education head of the department in Gauteng. “And that’s how my public service career was actually launched.”

Maseko also worked under Tambo’s protégé, Thabo Mbeki, when the diminutive, pipe-smoking intellectual was SA’s president. “Working with Mbeki was fascinating in many respects. He was one person who paid too much attention to detail for the head of state, so it meant that you had to know your story and be well prepared.”

They worked closely on government messages, for example, ahead of the post-cabinet meeting announcements. “So in my duty as government spokesperson, in most cabinet meetings, I would always steal a few minutes to just check with him:

“If this is my understanding of the decision, and it’ll always give the advice about what I should say.”

“I witnessed him operating in cabinet… you could tell that this was a man who was so involved, engaged, and concerned about issues of governance,” he said.

“I remember in cabinet, he spent a lot of time chasing ministers away if he was not satisfied that they’d done their homework. I had an encounter with him when I was presenting a proposal on a public works programme. I presented it to the cabinet ministers and he was clearly not happy. And then he sent me back to go and do some more work.”

That was not the end.

“And he called me on a Sunday afternoon to come and present a new proposal. I spent more than an hour within his office on a Sunday afternoon.

“Preparing for that meeting was also very stressful because if you’re talking about a subject, especially a topic pertaining to the economy, he would know 10 times more than what you do, because he did his own research. I found that to be very fascinating because it basically made me realise that it is absolutely important for everyone working in the public service to do their homework thoroughly and make sure that you are well prepared. I thought he was a disciplinarian.”

He was the chief government spokesman and CEO of the Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) during the Mbeki years, but when Zuma took over, his position became untenable.

Maseko’s crime? He refused to allocate R600 million from the GCIS advertising budget to Gupta media outlets. He fell foul of Zuma and was fired.

Maseko recalls learning through the news that he had been kicked out and replaced by Jimmy Manyi, a very controversial figure and close associate of the Gupta family. He went on to “buy” the family’s newspaper assets, including The New Age newspaper and TV channel ANN7.

The book is a journey through his life as a public servant and his early years under apartheid in Soweto, and ultimately what led to him blowing the whistle on Zuma and the Guptas when many chose to keep quiet. Writing the book forced him to deal with many scars from his past, including abuse at the hands of the apartheid system and police torture. He lost close friends and fellow activists, and escaped several attempts on his life.

But writing it was “very therapeutic”.

“I call it my third baby,” he says. “My experience with Zuma and the Guptas… at least it’s something that I’d spoken about quite a lot. But my other experiences in the struggle were things that I had locked up in my memory for more than 30 years.

“Writing my story gave me a chance to sit down and reflect on my life and experiences. Why I’m still alive today is a miracle. It’s something that I wanted to reflect on through this book.”

His life was turned upside down when he got a call from Zuma, leaning on him to help the Guptas, ahead of a meeting with Ajay Gupta, the eldest of the three brothers. In the book, he details an acrimonious phone exchange before he eventually met Ajay. Maseko was a kid during the 1976 Soweto uprising, who went on to be one of the youngest MPs in the first democratically elected parliament in 1994, representing the ANC.

“During the 1976 uprising, I wouldn’t even describe myself as an activist… I was just a kid who had just been exposed to the darker side of apartheid. I’m being told, as a 12-year-old, that you’re not going to be taught in English; you will be taught maths in Afrikaans.

“If the state had its way, they would have even insisted that my Zulu language must be taught in Afrikaans,” says Maseko during an interview in Rosebank, Johannesburg.

“The book is also about telling young people what it meant for my generation to be involved in the struggle and why what the Guptas did during the state capture period was something that was an antithesis to our philosophy or vision of transforming our society.”